Permaculture Zone Planner

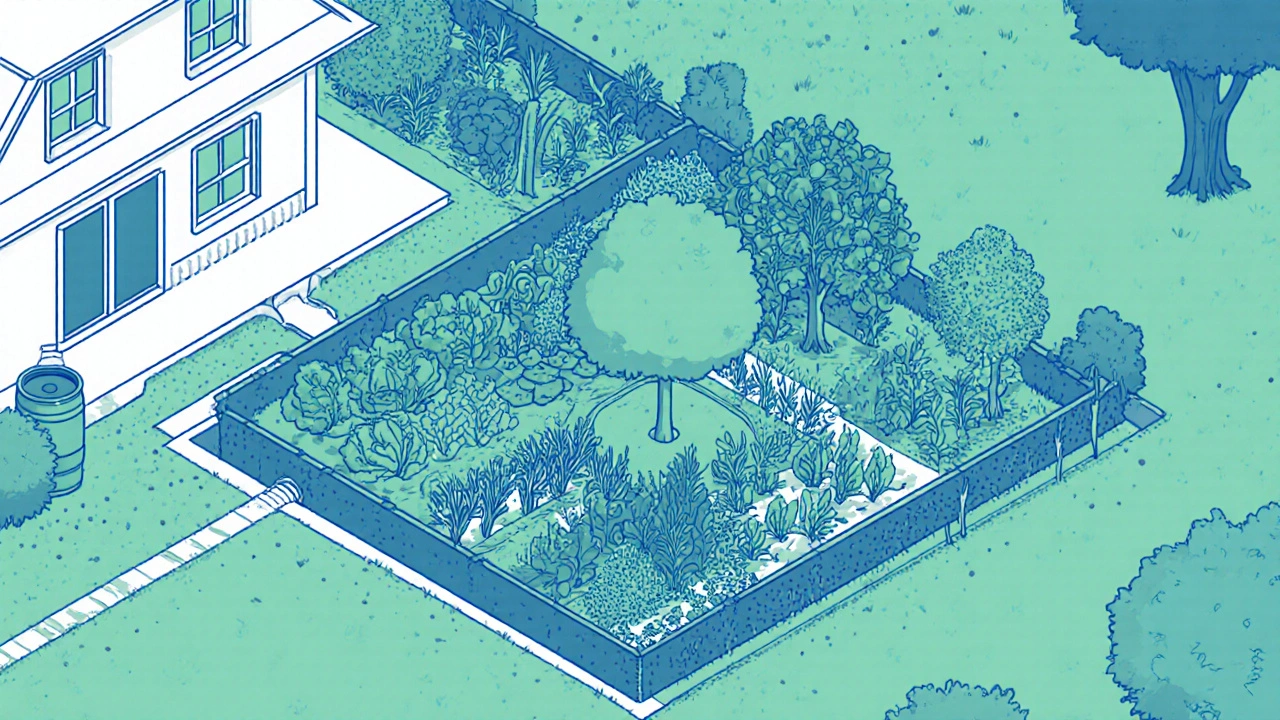

The Zone Planner helps you map your garden based on how often you need to visit different areas. Zone 1 is closest to your house (high maintenance), while Zone 5 is the wild edge (low maintenance).

Zone 1 (Closest to House)

Herbs, salad greens, and high-maintenance plants that need daily attention

Zone 2

Vegetables, fruit trees, and plants needing regular care (weekly)

Zone 3

Perennial fruit trees and bushes, larger crops that need less frequent attention

Zone 4

Wild foods, foraging areas, and semi-wild crops that require minimal attention

Zone 5

Natural areas that require no intervention, allowing wildlife to thrive

Imagine a garden that feeds you, protects the earth, and looks good year after year- that’s the promise of Permaculture Gardening is a design system that mimics natural ecosystems to create resilient, low‑maintenance food gardens. permaculture gardening isn’t a fancy trend; it’s a practical toolbox for anyone who wants to grow more while using fewer resources.

What is Permaculture?

At its core, Permaculture is a philosophy and set of design principles that aim to work with, rather than against, nature. The word blends "permanent" and "agriculture," but the scope is far broader- it covers energy, waste, community, and even economics. In a garden context, permaculture translates those big ideas into concrete actions you can start in your backyard today.

The Seven Ethics that Guide Permaculture

- Care for the Earth - protect soils, water, and biodiversity.

- Care for People - provide food, shelter, and well‑being.

- Fair Share - redistribute surplus, limit consumption.

- Observe and Interact - understand site conditions before you act.

- Catch and Store Energy - harvest rain, sun, and organic matter.

- Obtain a Yield - ensure the garden produces something useful.

- Apply Self‑Regulation and Feedback - adjust practices based on results.

These ethics become the compass for every design decision, from where you place a tomato plant to how you manage compost.

Key Design Concepts You’ll Use

Permaculture is built on a handful of repeatable patterns. Mastering them turns a chaotic plot into a thriving ecosystem.

1. Zones - Mapping Energy Flow

Zones rank garden spaces by how often you need to visit them. Zone Planning is a way to locate high‑maintenance crops close to the house (Zone 1) and low‑maintenance trees farther away (Zone 5). This reduces labor and maximizes efficiency.

2. Guilds - Beneficial Plant Communities

A guild groups plants that support each other. Think of a fruit tree (the "nurse") surrounded by nitrogen‑fixing legumes, deep‑rooted carrots, and insect‑attracting herbs. The result is healthier growth and fewer inputs.

3. Polyculture - Diversity Over Monoculture

Polyculture is the practice of growing multiple species together to mimic natural diversity and reduce pest pressure. When one species struggles, its neighbours keep the system afloat.

4. Soil Health - The Living Foundation

Soil Health is a measure of microbial activity, organic matter, and structure that determines how well plants can access nutrients and water. Compost, mulch, and minimal tillage nurture those microbes.

5. Water Management - Catch, Store, Distribute

Water Management is the set of techniques that harvest rain, slow runoff, and deliver moisture exactly where plants need it. Swales, rain barrels, and drip irrigation are the usual tools.

6. Composting - Recycling Nutrients

Composting is the aerobic breakdown of kitchen scraps and garden waste into nutrient‑rich humus. It closes the loop between waste and fertility.

Step‑by‑Step Guide to Start Your Permaculture Garden

- Observe your site. Note sun angles, prevailing winds, water flow, and existing vegetation over a week.

- Map zones. Sketch a simple plan, marking Zone 0 (your house) out to Zone 5 (wild edges).

- Improve soil. Add a 4‑inch layer of well‑rotted compost, then plant a cover crop like clover for a season.

- Harvest water. Install a rain barrel at the downspout, dig a shallow swale on the downhill side to slow runoff.

- Design guilds. Choose a central fruit tree (e.g., apple) and surround it with nitrogen‑fixers (beans), deep‑rooted carrots, and pest‑deterring herbs (lavender, rosemary).

- Plant polycultures. Mix lettuce, radish, and marigold in the same bed; they use different nutrients and attract beneficial insects.

- Mulch and maintain. Cover beds with straw or wood chips to retain moisture, suppress weeds, and feed soil as they decompose.

- Monitor and adapt. Keep a simple journal of yields, pest sightings, and water usage. Adjust plant placement or watering schedules accordingly.

How Permaculture Differs From Conventional and Organic Gardens

| Feature | Permaculture Gardening | Conventional Gardening | Organic Gardening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Philosophy | Systems thinking; mimics ecosystems | Yield‑focused, input‑heavy | Chemical‑free but often still plot‑based |

| Water Use | d>Catch‑and‑store, gravity‑fedIrrigation with pumps, frequent watering | Often relies on drip or overhead sprinklers | |

| Soil Management | Living soil; compost, mulches, no‑till | Synthetic fertilizers, occasional tillage | Compost and organic fertilizers, may still till |

| Pest Control | Polyculture, habitat for predators | Chemical pesticides, monoculture | Organic pesticides, but still monoculture often |

| Labor Intensity | High initial design, low ongoing effort | Continuous weeding, input application | Regular mulching, manual weeding |

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Over‑designing. It’s tempting to map every square foot. Start with a small test plot, learn, then expand.

- Ignoring the micro‑climate. A sunny south‑facing wall can create a heat island; place heat‑loving plants there and shade‑tolerant ones elsewhere.

- Skipping soil testing. Without knowing pH or nutrient levels you may add the wrong amendments.

- Relying on a single water source. Combine rain barrels with a backup well or municipal supply for dry spells.

Quick Checklist - Is Your Garden Feeling Permaculture‑Ready?

- Site observations recorded?

- Zones drawn and respected?

- Soil covered with organic matter?

- Water harvesting in place?

- At least one plant guild established?

- Polyculture beds instead of rows?

- Compost bin active?

Next Steps for Different Skill Levels

Beginners - Join a local permaculture meetup, start a single‑bed guild, and experiment with a rain barrel.

Intermediate gardeners - Expand to Zone 2‑3 crops, add swales, and try a small food forest.

Advanced practitioners - Map the whole property, incorporate livestock or chickens, and design a closed‑loop energy system.

How does permaculture differ from organic gardening?

Both avoid synthetic chemicals, but permaculture focuses on system design-zones, guilds, water catchment-while organic gardening usually follows traditional row planting with organic inputs.

Do I need a lot of space to practice permaculture?

No. Permaculture works at any scale, from balcony containers (micro‑permaculture) to large farms. The key is to design according to the space you have.

What are the most important plants for a beginner guild?

Start with a fruit tree (apple or plum) as the central element, surround it with nitrogen‑fixing beans, a deep‑rooted carrot, and herb companions like rosemary and lavender.

How can I harvest rainwater without expensive systems?

A simple rain barrel beneath a downspout captures runoff. Add a fine mesh screen to keep debris out, and use a gravity‑fed hose for garden watering.

Is composting really necessary for permaculture?

Yes. Compost turns kitchen scraps and garden waste into the organic matter that fuels healthy soil, closes nutrient loops, and reduces the need for external fertilizers.